L'avenir de l'éducation en Afrique : aligner l'éducation sur les objectifs de développement de l'Afrique

Experts have tackled Africa’s development challenge and elaborated various theories to identify the core of the issue. The reality remains that Africa’s development challenge is intricate and could not be abridged into any single theory. Nonetheless, critical areas of Africa’s development challenge could be examined, and solutions could be proposed to improve them. This is the case of education, which is essential to the continent’s development but does not garnish proportional consideration.

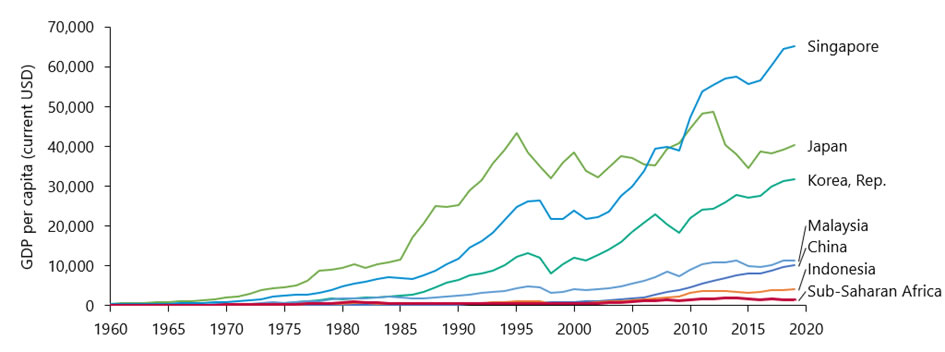

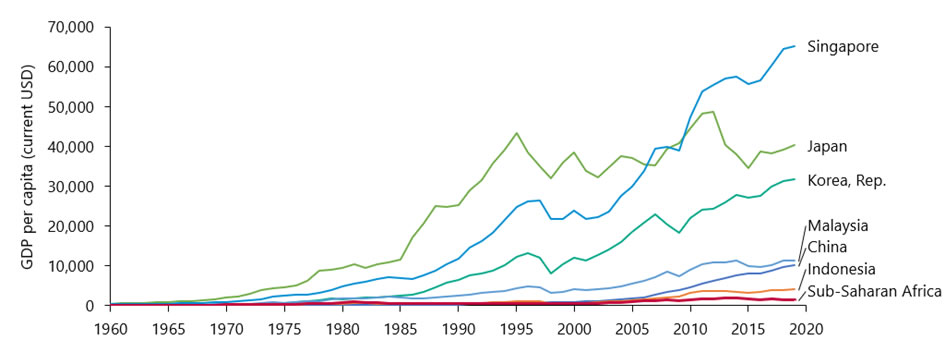

There is now sufficient evidence that indicates that investments in education may have significantly contributed to the economic growth of many Asian countries, particularly the East Asian countries, which are also commonly referred to as the High-performing Asian Economies (HPAEs). Industrialization played a central role in the development of these countries. Education in turn, fueled the growth of industrialization by supplying to industries an abundant supply of young skilled workers. This is, however, not the current reality in most African countries.

The challenges of education on the continent

In Africa, the situation is different from the HPAEs. While there has been an investment uptick in education, it has mainly been inadequate compared to the needs on the continent. Access to quality and affordable education remains a privilege on the continent, and the education system is not aligned with the development aspirations of most countries. Furthermore, the dropout rate remains high on the continent, and students are not necessarily learning when school. A survey once revealed that 80 percent of Sokoto’s Grade 3 pupils in Nigeria could not read a single word. In other words, 80 percent of the students in Grade 3 have completed three years of school and were still unable to read.

In Africa, the situation is different from the HPAEs. While there has been an investment uptick in education, it has mainly been inadequate compared to the needs on the continent. Access to quality and affordable education remains a privilege on the continent, and the education system is not aligned with the development aspirations of most countries. Furthermore, the dropout rate remains high on the continent, and students are not necessarily learning when school. A survey once revealed that 80 percent of Sokoto’s Grade 3 pupils in Nigeria could not read a single word. In other words, 80 percent of the students in Grade 3 have completed three years of school and were still unable to read.

Recommendations for a 21st century education in Africa

Africa does not need to reinvent the wheel in education because there are good, learned practices across the globe. In its African Economic Outlook 2020 report, the African Development Bank (AfDB) proposed a few solutions to improve education in Africa and ultimately enhance the economic outcomes of countries. The AfDB argued that countries should consider seeking harmonizing investments in infrastructure and education. For example, by targeting investment in affordable electricity in a village, students would benefit from more extended and more efficient hours of studying.

Also, the AfDB stated that the private sector could complement public financing in the education sector in Africa. Governments could leverage financing and technical expertise from impact investors, philanthropists, private firms, and entrepreneurs to invest in education. Finally, efficiencies could be further created in education spending in Africa. By performing audits and reviews and implementing checks and balances, the efficiency of public spending could be enhanced.

While these recommendations should undoubtedly help to improve education outcomes in Africa, the continent could adopt and adapt the education reforms that the HPAEs implemented to catch up faster with other advanced economies.

Increase investments in primary and secondary education

East Asian leaders understood early that human capital was their most important resource. They, therefore, focused on primary and secondary education. This strategy enabled the HPAEs to achieve two main objectives: generate rapid increases in the labor force and increase social welfare in the long term by preparing the population for lifelong learning and skills development.

In 1993, the World Bank Policy Research report released a report which revealed that in the mid-1980s, Indonesia, Korea, and Thailand devoted more than 80 percent of their education budget to primary education. To achieve the education spending equilibrium aligned with their economic development goals, the HPAEs only subsidized science and technology curricula at the post-secondary levels. These fields were more important for the large-scale industrialization ambitions of the countries.

Shorten education cycles

During his 2008 State of the City Address, Michael Bloomberg, the former mayor of New York City, stated that “College isn’t for everyone, but education is.” This statement is especially relevant for Africa, where poverty is proportionally higher than anywhere else in the world. Not all Africans need a master’s or a doctorate to earn an adequate income and a dignified life. Higher education is expensive, particularly in Africa. Ancillary education expenses such as transportation and school supplies contribute to making postsecondary expensive for students. As a result, even after families manage to enroll students into university, many cannot financially sustain the three to four years required for graduation.

Vocational programs as a feeder for the labor market

A vocational program is a type of postsecondary education that trains students for a specific line of work. A hallmark of vocational education is that it focuses on hands-on knowledge rather than theoretical learning. This differentiates vocational schools from conventional tertiary education, which is more academic and less job-focused. Vocational programs, therefore, generally require a shorter timeframe to complete. Furthermore, Graduates from vocational programs are equipped to begin working independently in their roles upon graduating. In fact, that is the objective of vocational training, and this is desirable for employers. Most industrialized countries have undergone a period where vocation education was a priority in their education system.

Although vocational programs take a shorter timeframe to complete, this does not exclude the fact that students can return to school and earn certificates or pursue other courses that will help them maintain their qualifications for an improved career path. With the increase in technology usage in Africa and the onset of massive open online courses (MOOC), it is now easier for students and employees to continue learning and improving their skills.

Adapt education to actual needs of African economies

In developing the curricula for education systems, African governments should account for established national development plans and projected labor force needs. Otherwise, students risk graduating with skills that are not aligned with the demands of the market. As much as individuals need to pursue their interests, these interests should be tailored to the current and potential demands of the market where the interests will be offered. Career interests also follow the laws of demand and supply. A psychology graduate in Japan is more likely to find a job after graduating than a Togolese graduate in the same field.

The education curricula should be dynamic

The school curricula in many African countries are outdated. They do not reflect the significant changes that have occurred during the past few decades in Africa and the rest of the world. The most visible consequence of this the poor quality of teachers on the continent. It also creates a cycle of poor learning, which is not nearly helpful in the labor market. Students study outdated materials and eventually become teachers who educate young students using an outdated knowledge base. The curricula in African countries should also account for the cultural aspects of education. The leaders of the HPAEs formulated policies for this. For example, while leaders valued Western knowledge, they preferred it to complement the established education framework in their countries. As a result, in addition to academic knowledge, the education systems in East Asia incorporated moral education concerning principles such as hard work, ethics, comradeship, and a common goal.

Education must become a strategic development tool for African countries.

Education is not a panacea for economic development. Nevertheless, quality education in a nation is a multiplier effect because it enhances productivity and levels the playing field for most people. African countries should leverage technology today and experiences from the HPAEs to provide a targeted and efficient education in line with national development goals. If Africa wants to industrialize soon enough, it must inevitably channel this vision through education by producing a highly qualified labor force in the shortest timeframe possible. Conventional postsecondary education will remain relevant, particularly for research, but the objective should be to provide people with highly relevant skills in the most cost and time-efficient way.